All it takes is a global pandemic for all the philosophy to come out. Though most of us are hard-pressed to describe a constant system of causality, that is, to trace actions or events definitely to what caused them, we suddenly must know. The virus must be so harmful as to justify our knowledge, a prime example of desperate measures calling for desperate times.

Even before the wet market and the outbreak and our collective gasp for breath, some appreciated the power of simple direct causation: “Vote Republican and my grandmother will die.” “Drive your car, and everyone will die.” “Teach that in schools, and everyone will die.” Death truly is the last refuge of the scoundrel and should be denied to him at all costs. Every personal and political decision in history has killed thousands, surely, and what we could have, should have done to preempt this Coronavirus is no different. But I am not going to the effort of putting pen to paper merely to laugh at consequentialist morality (an act, surely, that will eliminate some rare species of botfly from the heart of the Congo, etc.)—there is G·dliness to contemplate! (Animal soul: “Booo!” Me: “Can it, Sheldon!”)

The question is a simple one: To what extent does COVID-19 control G·d, and to what extent does G·d control it? We once discussed this in terms of Purim, the lottery, His face concealed and revealed in the nature of the day. The point, however, is profound enough, central enough to the difference between a G·dly and unG·dly life, to deserve a lifetime of contemplation (perhaps in this way we can fulfill the facet of divine worship called Mesiras Nefesh, self-sacrifice for G·d). Let us attack the question from a different angle called Hashgacha Pratis, individual divine providence, and the way Chassidic teachings transform the concept.

Individual divine providence means that G·d is actively involved in the universe at the level of each creation. It is a Jewish doctrine transformed by the innovation (revelation) of Rabbi Yisrael Baal Shem Tov, the Holy BeSh”T, a theological radical in all the best ways. It also, like many other principles of Chassidus (“G·d is everywhere” is another), is the way a typical eight-year-old in Hebrew school understands G·d. This childlike perspective is no accident. The simplicity of a simple Jew touches the simplicity of the Creator. But it would be a mistake to call the BeShT’s theology childish. It is nothing short of revolutionary:

“As explained by our master, the Baal Shem Tov, not only are all the particular activities of the created beings under Divine providence, and this providence is the life-energy of the created being that maintains its existence, but every particular movement of an individual created being has a connection to the intent of the creation as a whole…A slight movement of one blade of grass fulfills G‑d’s intent for the creation as a whole.”

from the discourse “Al Kein Yomru” 5696

Divine providence has historically been denied even by those who believe that G·d created the world from nothing. These are the deists and their ilk (in the straightforward reading) to whom the Alter Rebbe rebuts in the 2nd chapter of the 2nd part of the Tanya. Like other idolatry-adjacent beliefs, Deism derives from bad philosophy rather than simplemindedness. Because they imagine G·d can only cause effects through a close relationship with those effects (a limitation that only pertains to finite creations), they think divine involvement in His world contradicts His simplicity. They believe G·d abandoned the earth and is merely the ‘G·d of gods,’ the ultimate cause beyond, and today uninvolved in, nature. The response to this position, as the Alter Rebbe writes at length, is that creating something from nothing, on the contrary, necessitates the constant involvement of the Creator.

Jewish sages and rabbis, of course, have never denied G·d’s constant involvement in the creation, G·d forbid, just as all Jewish sages maintain that there is perfect and total divine knowledge. The debate has always centered around the extent and nature of G·d’s involvement in what He knows. Before the holy BeSh”T, some, like the Rambam, explained divine providence to rest only on individual people, but over all other species only in general. Per this view, G·d does not decree whether a specific fish should live or die, only that the species as a whole should survive, because it is only the species as a whole that is central to His plan. If the life of a single animal becomes a human concern, e.g., the peddler’s donkey dies and he suddenly has no more means of making a living, only then is G·d concerned with the individual animal. Even these sages seem to agree that the “chance circumstance” which rules over the lives of non-human creations is itself a decree of G·d, just as G·d decrees that human beings should have free choice. He decrees, in other words, that here something else should decree.

Opinions also vary as to whether there is divine providence over human beings equally. The Rambam in his Moreh Nevuchim (The Guide for the Perplexed) says providence is a function of the intellectual bond between man and G·d. Thus fools and evildoers are separate from total providence and left to some extent in the hands of nature just like other species.

The Chassidic doctrine of individual divine providence first introduced by the Baal Shem Tov is genuinely original, at least among the stated opinions and known philosophies of the Torah that have reached us. Although previous Jewish sages strongly support both G·d’s omniscience and, possibly, His constant creation of the universe, the holy Baal Shem Tov came and revealed a new light, a new facet of the Truth. G·d is involved in every aspect of the creation, and every aspect of the creation contributes to His plan for the entire universe.

In the Baal Shem Tov’s world, there is no room for chance.

But what if we are not stones or donkeys or even wicked fools? What if we are righteous, deserving of individual divine providence according to all Jewish opinions? Is there any innovation, then, in the Baal Shem Tov’s light?

A further wrinkle: Hashgacha, divine providence, as so far discussed, is a doctrine drawing G·d closer to mundane worldly realities; hence the Rabbinic hesitation to embrace it fully, for fear of contradicting His simplicity, His transcendent perfection. Providence, in other words, means G·d is involved even where He’s not expected, in the affairs and logic of finite and worldly things. But a Jew intertwined with Torah and Mitzvos, with the divine Wisdom and Will—what use does this Jew have for providence? The Creator shows Himself openly and directly in their G-dly affairs, within their holy pursuits! Per the sages before the Baal Shem Tov, providence is needed specifically where it will not go, to the mundane and the separate. And even the BeSh”T, who says there is providence for sinners, does not seem to explain why the non-sinners need it. A saint, a holy Tzaddik, does not need G·d’s hidden machinations; his very soul is a revealed instrument for the divine!

Which makes it strange to read the words of the Rebbe Rayatz. The 6th Rebbe of the Lubavitch dynasty, R’Yosef Yitzchak, a leader of the Jewish people whose very life was the Jewish practice and education he spread under the deadly watch of Stalin and the KGB makes a remarkable statement about his imprisonment, torture, and commuted death sentence in 1927. He says that if it had not been for his discussion of the Baal Shem Tov’s doctrine of individual divine providence in the discourses of Rosh Hashana of that year (תרפ”ז), he would not have had the strength to withstand his imprisonment.

To which, three questions:

(1) Every Rabbinical opinion we know would agree that the Rebbe, a saintly Jew who gives his whole life to the service of G·d and the Jewish people, experiences individual divine providence. So why was it the Baal Shem Tov’s doctrine, precisely, that gave him strength?

(2) Why is divine involvement in private affairs even relevant in this case? The Rebbe’s entire existence is a public devotion to the betterment of the Jewish people and the furtherance of G·d’s Will and Wisdom on earth. His life is inseparable from G·d, regardless of G·d’s involvement in mundane worldly affairs.

(3) Even if we wish to propose that the benefit of his contemplation of providence is finding G·dliness even in his enemies and imprisonment, why is providence the object of his thought? The heartening concept that finds G·d even in terrible oppression is “everything that comes from G·d is good”! Hashgacha Pratis, individual divine providence, merely says that G·d is involved, not that the bad is good. Under providence alone, we might say that G·d is involved in the thing, but it is indeed a harsh punishment or a bitter exile!

Indeed, there is an implicit tension between questions (2) and (3). If the Rebbe Rayatz’s whole life is one with public service in matters of Torah and Mitzvos, if his entire being is about G·d and not about himself, why would the apparent evil of his enemies and imprisonment bother him at all? We are speaking of a saintly Tzaddik who risked his life day after day to serve the Jewish people. The holy Rebbe had little concern for his wellbeing in a state of literal self-sacrifice. He was like the holy Rabbi Zushya of Annipoli, who said to the student sent by the Maggid to learn from him how to accept suffering with joy, “I lack nothing and have never suffered!” Such souls do not feel difficulty, do not feel pain, do not feel stress. Why does the Rebbe need to contemplate individual divine providence in the first place? On the contrary, like Rabbi Akiva, a Rebbe is grateful for the opportunity to give up his life for G·d!

Rabbi Akiva, however, who yearned for self-sacrifice and even to die for the sanctification of G·d’s name, is not the only Jewish path. Avraham, Abraham, our father, did not seek out self-sacrifice. His total devotion to G·d expressed in the spreading of monotheism. If this devotion called for self-sacrifice, he was willing to give up anything (indeed, even his divine mission itself, which is the secret of the Akeida, the binding of Isaac), but he did not seek it out. Thus, when Abraham sat in prison, he would not have enjoyed it. It would have been an interruption to his life’s mission of spreading the worship of the One G·d.

Thus, the Rebbe’s pain is like Abraham’s pain. The existence of a holy Jew is one devoted to G·d and others and especially to connecting others with G·d. In this mission, the personal risk or threat of bodily harm concerns the Tzaddik not in the least. (And here, the FIRST LESSON: to focus on helping others in the time of crisis will lessen our pain.) The righteous Jew is instead pained that his self-sacrifice might interrupt his holy work, might imprison them where they are unable to carry out G·d’s Will (here, a SECOND LESSON: where we can do G·d’s Will, we are free). It does no good, either, to say that because the Rebbe is now in prison, being in prison is now G·d’s Will. A Rebbe is not G·d’s employee, merely contributing to the cause to the best of his ability. The Rebbe, the Jew, is co-owner of the enterprise. Owners are in it for the result, and no to absolve themselves of responsibility. If the Rebbe is sitting in prison, he may not be guilty for his inability to spread G·dliness, but it still hurts.

Facing a global pandemic, and at any other time, there are two types of souls, each with its distinct mission. One gives itself over to fulfilling the task to the very end, no matter the coast, but in the end, once all effort has been expended, it feels no pain. All is by G·d’s design. He planned and expected the whole story, not just my part, but whether the thing will succeed at all—so why should I worry? So do faith in G·d, and the faithful execution of my responsibility, make for peace of mind.

Then there is the Jew who cannot rest, who is so bound up with G·d that G·d’s Will is his will. The Jew does not serve than then wash his hands. The Jew is a piece of G·d; G·d’s concerns are not merely his mission but his entire being. Never mind what G·d expects of me—what does G·d want beyond my responsibility? The job is on pause. It hurts.

(We see it in the story of the Rebbe Rayatz’s father, the Rebbe Rashab, in Petersburg, at a rabbinical council. He witnessed the Tsar’s ministers attempt to coerce the gathered Rabbis, with the threat of pogroms, to agree to secular education for all Jewish children. The Rebbe spoke so vociferously against the idea that he fainted, and his words were so pointed he was placed under house arrest. Once the Rebbe was freed, one of his rabbinic colleagues came to visit and found him weeping. The Rabbi asked, “Lubavitcher Rebbe, why are you crying? We have done everything we could do!”

The Rebbe replied, “But we still haven’t accomplished it…”)

Those with no faith, who do not believe G·d controls our affairs and whose lives are egocentric, feel pain when the crisis exceeds their ability and expectation. Those with faith whose lives are devoted to G·d in the selfless pursuit of the mission and who know G·d’s total control of all things feel peace. But those with faith, who know G·d controls our affairs, but for whom G·d’s mission is their very self—the crisis causes them pain, not because they are pained but because G·d is pained. They do not say, “G·d has other messengers to accomplish the mission.” Such false humility has no place in the inner spark of G·d that knows if its assistance were unnecessary it would never have been brought into being.

Thus, the THIRD LESSON: Pain in the faith of the crisis does not necessarily reflect a lack of faith. If we feel the pain, we should make it that pain that, as the Rebbe Rayatz says, the Baal Shem Tov’s doctrine of individual divine providence can heal.

As every chassid knows and rushes to explain, the descent is for the sake of an ascent. The concealment of G·d is that He may reveal Himself further. The essence of “Cursed is Haman” is “Blessed is Mordechai.” Moses doesn’t enter the land and passes away in the desert so that Moses’ work may become the possession of the entire nation. The darkness exists for the sake of greater light.

And yet, the darkness is still darkness. Jail time is by definition time spent not spreading G·dliness or helping Jews, despite all the inspiration that may eventually come from it. The virus is a killer and a terror, even though so much good might emerge from it. That’s why it still hurts. That’s how it yet, in its way, has control, yet denies G·d.

Unless you believe the Baal Shem Tov. The holy BeSh”T says that not only is every detail of the creation in G·d’s control, but every particular fulfills G·d’s purpose for the entire universe.

What is critical, in other words, is not that the BeSh”T extends individual providence to every detail of every creation. What matters is why. Until the Baal Shem Tov, divine providence was a hierarchy. The Rambam says individual providence is a function of the extent to which something understands G·d. The righteous have more providence, the wicked less. The enlightened more, the benighted less, a rock none in particular, for it knows nothing of G·d intellectually. A virus is more rock than a human being…Comes the holy Baal Shem Tov and reveals: Not only is every detail of each thing from G·d. Not only is it all by G·d’s plan in general. But each creation itself fulfills His general plan for the entire creation.

The Baal Shem Tov is no longer talking about G·d’s plan and the human being, as not-G·d, dealing with it, being at peace with it or feeling pain because it’s on hold and we are helpless. The Baal Shem Tov’s divine providence, at the fiery heart of Chassidus, is that there is nothing to fear but G·d alone because there’s nothing but G·d alone. The BeSh”T says if we have no pain but G·d’s, then there is no pain anywhere, for G·d’s will is everywhere fulfilled and nowhere unfulfilled. Light has no privilege, is no speedier or more direct a fulfillment of G·d’s plan, than darkness. The Rebbe remembers this and thereby makes from his imprisonment itself a G·dly perfection. The Soviets themselves decided to set him free. G·dliness did not merely emerge from the dark. The dark was G·dly and did not have to become light to be so.

The FOURTH LESSON: There is no despair in this world. G·d is not merely its Creator, not only deeply involved in it but equally present in all aspects of all creations beyond by our understanding of their natures.

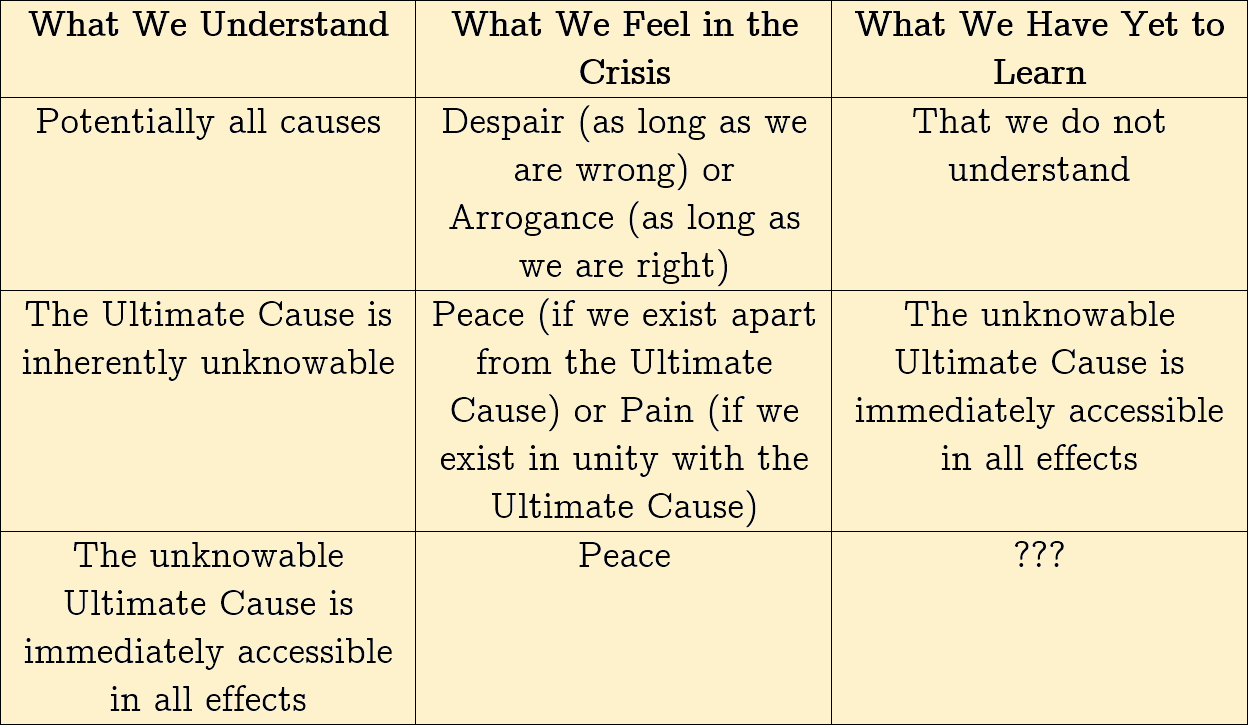

Those who have not yet tasted the taste of Torah think that effects derive from comprehensible causes. In the crisis, they are either crushed (if wrong) or arrogant (if right). Until the Baal Shem Tov, those who made their will G·d’s will knew that their lives were the effect of an incomprehensible Cause, but the effects themselves were still comprehensible; dark is dark, no matter the light that emerges from it. The BeSh”T reveals that you understand the darkness as little as you know G·d because the darkness is just as immediate to G·d’s unfolding plan as the light, a direct and necessary fulfillment of His purpose for the entire universe. What you think darkness and light mean, they do not mean…

This freeing ignorance, this relinquishing of judgment, this disappearance of contradictions to G·d’s plan—this is the real freedom. We do not and cannot know what the virus is; all we can know is that it cannot contradict G·d’s highest and deepest intentions, any more than a thing can hide behind itself. The Creator is just as concealed by the virus as He was by the status quo ante. Whence despair?

We are bound up in the life of the living G·d. We have a mission. Nothing stands in our way. Let us proceed, without delay, to the immediate and complete redemption, when these truths will be as common and straightforward as a sour headline.

Based on the Rebbe’s renowned letter on Hashgacha Pratis, Igros Kodesh vol. I p.168ff and the Rebbe’s sicha for the 12th of Tammuz, Likkutei Sichos vol. XXIII p.157ff.