Beneath the needled boughs on the banks of the Tagus. Why ever move again? The air is cool and breezy off the mighty estuary. Gulls croak all around. Behind is the bustle of Lisbon, the distant breath of automotive traffic, the clashing of a pot in a restaurant no-doubt desperate for off-season custom. Today is a good day; it isn’t raining.

Why ever move again? The Ponte Vasco de Gama, longest bridge in Europe, unfurls to my left like a misplaced spasm of Louisiana, a momentary whiff of Pontchartrain and beignets and bayou. The cable car to the oceanarium drifts silently overhead. It is impossible to wonder with anything more than the curiosity of the content whether today they have any takers. Calm waters and limpid skies give way at the horizons to clouds, not the droning omnipresent gray of Sunday but white cotton East toward the rest of Europe, and upriver, future rain-bearers. One of the restaurants has hung chimes which soften the squeaking and clanging of walkers along the promenade, their presence just constant enough to remind me I am not outside of civilization but on the edge of a pocket of peace folded against its loving bosom.

The bridge crosses the river so I don’t have to. Why ever move again?

It is possible to step on the Vacso de Gama bridge and walk to Vladivostok without your feet leaving pavement. But Vladivostok is only an idea in Lisbon, an implausible theory. If I was the bridge, a simple unprepossessing miles-long concrete structure, I could have Russia implicitly. I would in some sense run there at every moment, be there by being in Lisbon, my body my grandfather’s whom I have never met.

But I am not even the bench I am sitting on, nor this pen, nor even the fingers manipulating it. I’m certainly not the distant dirty-snowed port, salmon and cod by the millions failing to warm its air. If I want to cross the river, I have to move. I at the very least have to move my thoughts. But why ever move again?

“Your body will need something eventually,” a voice within threatens. Perhaps. But perhaps I reject the notion. Adam didn’t need in Eden; courageous Korach didn’t need in the wilderness. They were perfect just as they were. Perhaps I will waste away here on the bank of the river, because it is an insult to beauty and G-d’s creation to need anything, a rejection of the lapping waters and the moment in which they lap and all else that fills it. Motion is betrayal. Maybe I will die here with honor, the empty bench remaining as a testament to my discovery of G-d right where I sat.

As the sages or King Solomon might connote, and as I’ve been trying to say for a few paragraphs: existence is suffering. And as father Avraham teaches us, my still death beside the Tagus would itself be a motion, a furthering of my existence, a departure from the non-being I smell within the infinitesimal fraction of here and now.

It is no simple thing to cease to be accessible at your own metaphysical address, to rig your front door so that when they batter it down they meet nothing but G-dliness. An accessible existence is a notoriously difficult thing to dispose of. When Descartes said cogito ergo sum, I think therefore I am, it was with a note of triumph, having ascertained that there was at least one thing he could not doubt, namely the existence of the one who was doubting, i.e., himself. He should have mourned. The prisoner cannot free himself. Actions grounded in our own knowing are grounded in us and so no matter their apparent valence shall always reinforce our existence.

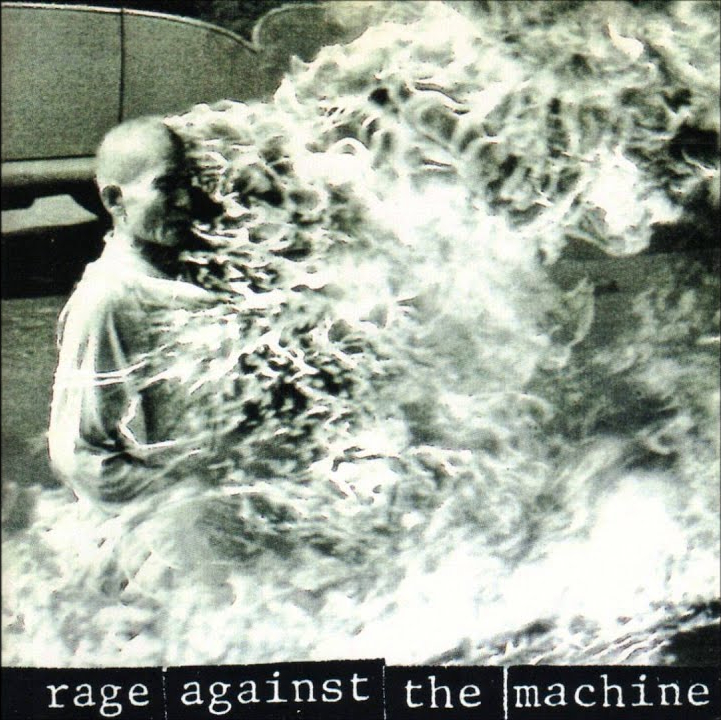

Martyrdom is no escape. A monk sets himself on fire in protest. His form is lost in the flames; his soul passes from the material realm. His existence is no longer accessible, not as itself…right?

Do we not find the monk’s existence immortalized through his actions? Is he not found, there in the heart of his protest, for all eternity? He has become part of something larger than himself; he has traded a small mortal form for the form of the idea. His existence is now eternally accessible, more easily found. It is a martyrdom of self-extension.

The call sign of this self-perpetuating martyrdom is its logic. The human condition: our “independent” selves are functions of other selves. I’m bigger than little brother but smaller than father, smarter than a fifth grader but dumber than Einstein, a giver to students but a receiver from teachers. The tie that binds, the triangulating system binding us to other nodes in the web of being, is logic.

When the monk sets himself on fire, he does not sweep his locus on the web clean; on the contrary, he ascends to the state of pure logic, his node full of web. “The tenets of my religion define me,” he said before he was burned. “There is nothing here but the tenets of my religion,” he says now.

The node is not empty; it is so full as to merge into its surroundings. A living monk may sever the connections, shift his position, leave Buddhism for atheism or Sikhism. A martyr of self-extension has locked his logic into place. He has moved beyond being a single thing among all finite concatenated things, and become a principle of concatenation, an idea, infinitely more present, undying.

In other words, death and life are not continuing and ceasing to be in this world. Being is to be in the web of logic. Death can reinforce and intensify this being. It is not, itself, an escape.

Avraham is the first to break free of the web, to wrench himself free, to non-be. Our father rebels against all his holy logic by binding Isaac upon the altar. In his mad devotion to G-d he sets aside his beliefs and religion and the extension of his line. When logic tells him “G-d promise a nation through Isaac,” that his son and he are tied by the web, Avraham ties his son and thereby cuts the connection. When logic tells him G-d does not desire human sacrifice, he turns away. When it insists that martyrdom is only for a cause, Avraham is willing to not be a martyr, then. There is no ground for the sacrifice of Yitzchak in what Avraham is. On that mountain he exerts none of his own logic.

Is this not the very inscrutability of G-d made manifest? When Maimonides writes that we cannot even affirmatively say that G-d exists, what he means is that G-d is not a being of the web. He exists only because He is himself, relative to no other thing, and so the verb “to be” means something incommensurately greater in his case. Avraham is only able to be nothing before G-d by dint of the G-dly nothingness within. He is not nothing by external relationship to the Creator (a further web) but by faith, the inner path, a capacity built into his very being.

If he is not defined by any web, what remains is not more of Avraham, but none of him, which is also, absurdly, Avraham— the deepest truth of Avraham, his G-dly truth. He found it not through stillness and death. He found it by riding to the mountain on G-d’s command.

Why ever move? Because it is the only way to stay still. Why abandon this moment here, where the birds of prey swing low on the winds of the continent to hunt the glassy blue waters? It is the only way to keep it.

November. Dusk. Lisbon.

All the demons here

are my own.

A million moorish tiles weeping.

Strangers on the Praça offer hashish and cocaine in stage whispers.

Dark cobbles, dark thoughts.

The square was urbane, European, and soothing

before I learned

from the Bubbe in the purple bonnet

urging me to plunge my youth

into the city

before the single synagogue

is returned by demographics and economics

to the post-Inquisition peace

with the pogrom.

Here they burned the Jews.

All the demons here

are my own.

The Jews of Lisbon saw the waters of the Rio Tejo from the Praça do Comércio before they were burned at the stake. They were no mere martyrs. They were descendants of Abraham, torn from the web, instantiating the inner G-dly void closer to them than any logic or definition.

There was, in the preceding silence, a perfection against which there is no rebelling, a stillness that could not be moved. There were no bodies that hungered, no directions to reach in, no seconds to measure. Why ever move?

Then, a sigh, and there was light.

Abraham Akeida alone faith melancholy sacrifice travel trust