Two souls meet, one ascending after a long life in this world, and the other descending to be born. “What’s it like down there?” asks the descending soul.

“Well,” says the ascending soul, “have you heard of Tzitzit? Down there, Tzitzit only cost a few kopecks.”

“Only a few kopecks!” exclaims the descending soul. “Why, Tzitzit are the marvel of heaven, the praise of infinite angels!” The soul throws itself downward, hurtling toward life.

“Wait until you hear what you have to do to earn those few kopecks, though,” cries the ascending soul…

-A Chassidic Tale

The New Yorker has given a platform to the ideas of David Benatar, an anti-natalist philosopher arguing that it is better never to be born than to live and that the human race should go gently into that good night without having children first. An Indian man has already taken this philosophy so seriously as to sue his parents for the damage of creating him, an extortion tactic reminiscent of the rock star in one of Douglas Adams’s novels who spends a year dead for tax reasons.

Jews are inclined to laugh at this philosophy and the resultant antics. It is hard, in fact, to imagine a less Jewish philosophy that did not involve overt idolatry. We are the faith that brought the world the Imago Dei and the exhortation to “choose life.” G-d is the G-d of life in Judaism, and He commands humankind, before all else, to perpetuate their own presence on earth. Like all Torah laws, this commandment is binding upon the Jew whether they subscribe to trendy philosophies of despair or not.

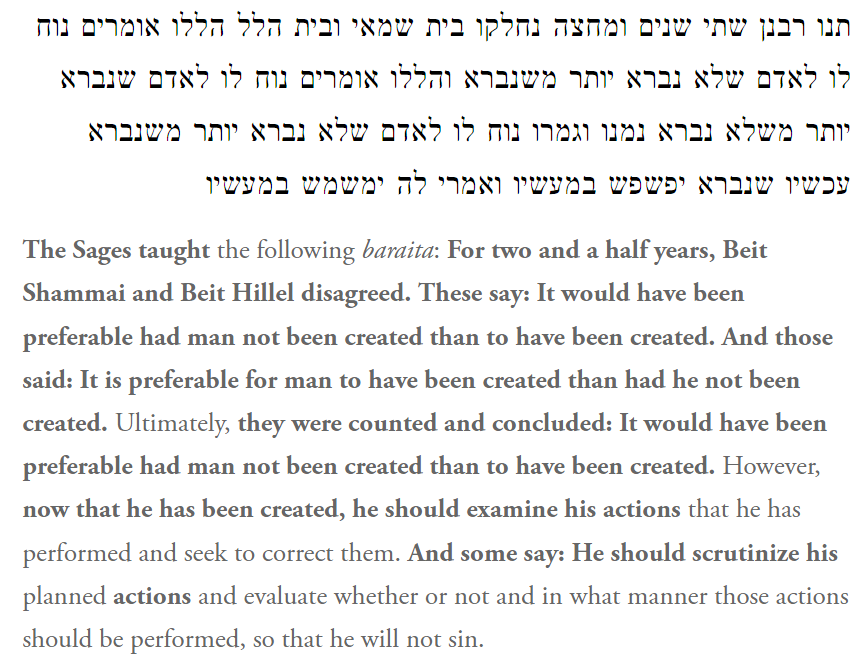

The Mishna in Pirkei Avot, however, does give a mysterious nod to not wanting to be born: “Against your will you live,” Rabbi Elazar HaKappar teaches. And then there is this passage from the Talmud:

[Source]

In this debate between Hillel and Shammai, Shammai wins; everyone agrees in the end that “it would be preferable had

What is so great about life anyway? After all (and contrary to popular myth), Judaism has a rich conception of the before- and

What, then, is accomplished by being born? One old answer expressed in different ways in different places is that we are born for our own benefit, that is, to actualize some potential within our own souls. Being born allows one to be better and more perfect than is otherwise possible, and to achieve greater states of spiritual existence than are otherwise possible. True, the soul may start at a great spiritual level, but life in this world improves upon than level and brings us new perfection. Thus, being born is a gift. Call this answer the old answer.

There is also a new answer, the one that makes room for the anti-natalist position. Of course, anti-natalists don’t argue against being born because they think the alternative is the soul’s perfection before G-d, but because they think it is simply better not to be than to be at all. If we are consigned to existence regardless, whether within a body or abstracted away from one, then being born may perhaps be an opportunity to improve that existence. This is what the old answer said.

But if being born is the very act by which we exist, then how can it be said to improve upon what we were before birth? Before we were born (or conceived, or what have you) we simply did not exist, and after we die we shall not again. Rather, all of life’s benefits must be judged on life’s own terms, not by what life accomplishes for a soul that persists after death, but rather what life accomplishes per se. This is the new answer: being born accomplishes being alive. Astutely, David Benatar assesses being alive, sees a lot of suffering, and seeks a return to non-existence.

The Talmud agrees with neither the old answer nor the new one. As in so many areas, the new answer is right to judge things (in this case, life) on their own terms, but the more superficial ancient reasoning (that life is justified by the perfection of our broader existence) is correct in its conclusion — to choose life!

The houses of Hillel and Shammai argue all over the thousands of pages of the Talmud, and most of their debates share a common denominator[i]: The disciples of Hillel follow the actual, whereas the disciples of Shammai follow the potential. The classic example is in the laws of Chanukah. Hillel says we light one candle on the first night (and this is the law we follow) whereas Shammai says to light eight candles on the first night. The former wants always to act on what has already come to pass, whereas the latter wishes to act on what remains to be done.

So, too, in their argument over whether it is good for man to have been created. Both houses agree that man’s creation, like the rest of the physical universe, brings no perfection to G-d. Their disagreement is whether the soul is

The House of Shammai says it is not good for man to have been created, for there is nothing gained for the soul in this world that the soul does not already possess in potential. Their position is more closely aligned with the new answer (unsurprisingly, as Shammai’s way of thinking is described as messianically progressive) — that

Hillel, on the other hand, argue it is better for man to be created, that the soul benefits from being embodied, that actualization has inherent value over potential, and we should look at life as an opportunity to raise ourselves higher in ever-greater perfection. This roughly parallels the old answer, which says that embodied creation serves our broader existence beyond the body.

Both Hillel and Shammai, however, believe in being born, as Judaism necessitates, for neither position is ultimately beholden to what is good for a human being. Even though Shammai win and the Talmud expresses a form of “anti-natalism,” never are we directed to pursue merely what is good for us when we are born. The entire debate of Hillel and Shammai concerns only what is “preferable” for man, in man’s own terms, in terms of human self-betterment, and that is why Shammai wins.

Or: If Judaism reduces to a question of self-perfection and self-benefit, there is room to argue for nihilism, to turn to the “Utter futility! All is futile!”, for G-d’s ways are inscrutable and His Torah concludes that we will never in our lives compare to the spiritual state of our souls before we are born.

Or: The “meaning” in a meaningful Jewish life does not necessarily mean very much if that life is a self-actualizing or -fulfilling existence taken on its own terms.

The only matter on which there is no debate is that it is good to be born and to cause others to be born because G-d wills it. It is only when life is for Him that life becomes inescapably meaningful. “Now that he is created, he should examine his actions” — for it is only by acting in service to G-d, our sages knew, that being born is justified beyond the question of potential and actual.

Perhaps most powerful of all, once we see ourselves as existing merely to serve our Creator, we can even admit that the House of Shammai is right, that there is wisdom in David Benatar’s argument. To live life merely for an afterlife is to define life away, and

[i] For all of the following on Hillel and Shammai’s debate, and much more, see Likkutei Sichos vol. XXII, second Sicha of Shmini.

[ii] By “creation” we here refer to the verb used in the above-quoted passage in the Talmud implying creation ex nihilo, existing apart from G-d as an ostensibly separate being. The human being is thus “created” when the soul is embodied, prior to which the soul exists in a state of (at least relative) nullification before G-d. This understanding of “creation” is consonant with the view

[iii] i.e. the existence of the soul apart from the body, including the beforelife and the world to come,

afterlife anti-natalism chassidus meaning philosophy purpose

Yasherkoach Tzvi! Thought provoking!