The year is 1877. Cornelius Vanderbilt and Brigham Young recently passed away, New Hampshire just became the last state to allow Jews to hold public office, and, on the other side of the world, in White Russia, Rabbi Shmuel of Lubavitch delivers a famous series of discourses on Chassidic thought.

Your friend Richard walks into your well-furnished Boston parlor hefting some kind of canister, which with the obscurity of distance and a bit of wishful thinking you imagine to be packaged whiskey (perhaps he arrives from Jack Daniel’s Tennessee distillery, which just turned two years old). All hopes of drunken frivolity flee your mind, however, when you see the stern visage with broad forehead and wide lips staring at you from the side of the cardboard cylinder. Under the portrait, a florid signature acts as a mark of authenticity. It reads “Thomas A. Edison.”

Without explanation, your friend uses your best letter opener to lever the metal cap out of the cardboard tube, carefully upends the whole thing on the table, and lifts it away to reveal…something. It looks like a thick, hollowed-out candle, and its outer surface is covered in thin grooves. Your friend declares, bellows to mend, that you are looking at sound.

Finding this overly Sinaitic, you stare.

“Edison,” he presses on, “has found a way to record sound.”

You risk a glance at your European piano (I allow you, for the purposes of this exercise, to be fabulously wealthy) stacked high with recorded sheet music. Your friend seems hurt.

“It’s not just the notes he’s recorded. Those are used to create new sounds. He’s gone and recorded old ones onto these wax pieces, and with his new machine, you can hear them again.”

“New machine?” you ask.

“He’s calling it a phono…phono something. Isn’t it the bulliest thing you ever heard?”

Eager to wipe the smile off his face (you really like your letter opener) you say, “Impossible.”

He frowns. “I heard it myself. He cranks the machine, and it reads those notches on the wax there, and music comes out of its horn.”

“Who ever heard of a machine reading?”

“You just did.” He thinks that this a great point and grins like the cat’s uncle. He doesn’t know that your great, great grandfather Thaddeus was already rolling his eyes during the declaration of the Declaration of Independence, thereby bringing cynicism to America. Richard is destined to lose this exchange.

“Why should I care?” you ask with an attitude your descendants a century and a half from now will be proud of. “I don’t need any machine. If I want to hear music, I play it, or I find others to play it for me.”

“Oh, everyone knows you spend hours holed up in here with your drink and your piano-”

“If there is a better use of my time I’ve yet to discover it.”

“It’s not that. Don’t you want your music to spread out across the divide?” asks your friend.

“What divide?”

“Why, the one between yourself and everyone else, of course! What good is your music if only you hear it?” He crouches next to the cylinder, admiring it. “With this, the whole world can sing.”

First there wasn’t an existence, and then G-d created one. Before that (Augustine would tell you if you asked) He was preparing hell for those who pry into mysteries. Douglas Adams said with authority that the creation of the Universe “has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move.” But unfortunately, it’s here. We might as well deal with it.

We are told that He had a hard time creating it all. He’s infinite, you see, pretty much by definition, i.e. G-d(n.): He who caused everything else to be and was not caused by anything else to be. So He must be infinite, since if He’s there before everything else exists and He’s not infinite, we have to wonder what else is there, how it got there, where it gets off not being either G-d or G-d’s creation, etc. It would be terribly out-of-place, since no place or time had yet been created. But I digress.

The problem with being infinite is that all You see is more of You in every direction. If you want to create something that is decidedly not You, say, a slice of pizza, you have to make room for it. No problem, you say. Being infinite has its advantages; you’re infinitely powerful. But now – what do you make the pizza out of? It’s fine, You think. I’ll make it out of my own infinite existence.

A slice of pizza made of infinitude sounds great at first (people would have probably been less angry if the universe were any kind of pastry) but: 1) If it’s infinite, what makes it pizza and not G-d? Isn’t pizza by definition limited to being pizza and not, say, a giraffe? You can’t make these fine distinctions. All you have to work with is Infinitude, and whatever that is, it probably doesn’t come with cheese and sauce. 2) Once you have this pizza, where are you going to bite into it from, wise guy?

It seems G-d can play an infinite symphony for Himself, but he can’t record it. The music is one thing, an expression of G-d as He truly is, what we call His Infinite Light, whereas the recording is quite another, bringing G-d somewhere that’s not Him. And “not Him” is in short supply. Even if he uses his infinite power to make that pizza, on the grounds that he can do anything, it won’t help: it would be like listening to an iPod at a concert, where the weak recording of the music is drowned out by the real thing and ceases to be audible. Besides, what use is a recording that only exists on condition that the musician continues to play? Why can’t He create something separate from Himself that exists on its own terms, without the need to bring his infinite power to bear? If the pizza can’t just be delicious without having to constantly reflect G-d’s involvement in its creation, is it pizza? Or is it still G-d’s ephemeral symphony known only to Him?

He really can’t seem to escape Himself.

The wax cylinder begat 78s, and 78s begat 45s, and humanity rejoiced, for a mere century after Edison’s invention they could listen to ELO whenever they desired. The technology involved in the successive generations of records was essentially identical. Edison discovered that by translating the vibrations of a diaphragm to grooves on tin foil he could later reverse the process, vibrate the diaphragm in the exact same way, and reproduce the sound. It is quite astonishing that such a crude process should work, and no one was more surprised than the great inventor when he first heard his machine say “Mary had a little lamb.” The phonograph was born, and with adjustments, the modern turntable followed a few years later. Sound was captured.

But was the whole world really singing? Sure, you had music in your living room, no multi-million dollar stage shows or spandex required. But if you wanted to hear “Sweet Talkin’ Woman” as you sat in the park, dodging occultists and penning a letter to President Carter, you were out of luck. Even at home, your records were large, fragile, and subject to decay, all concerns since the original phonograph, though mitigated in part by technological advances.

We see a general principle at work here. Any form of communication, whether by sound, light, or other means, must lose something in transmission when translated to a different time, place, or person. In other words: it is impossible for another to know something as it knows itself. This is why it takes the best of poets to fit even the wispy edges of our experience into dead, fragmented words. It is why in the ancient High Court of Jerusalem, instead of sleeping the night before a capital decision, they would stay up until dawn, debating, reviewing their opinions, lest they forget. How could they forget, asks the Talmud. The words of the judges were recorded by two stenographers, it’s true, but words on paper can never convey a full line of thought, as anyone who tries to review their notes at the end of a school term will unfortunately find. If it is thought, it cannot be expressed in words. If it is in words, it is no longer thought. If it is emotion, it cannot be put into musical notes. If it is music, it is not emotion, and only those artists at the heights of their powers can approach leveling the difference. Once the music is performed, the rule holds sway once more. A performance is not a recording, and a recording is no longer a performance. If this miscommunication principle were not true, speech wouldn’t be necessary at all; you could know my thoughts as I know my thoughts. If you could know that, what would be the difference between you and me? If there is nothing lost in transmission, we are not communicating, we are one. If we are not one, then we communicate.

Therefore, when Richard unveiled that cylinder for the first time, you were dubious. Once you heard the gramophone sing, you scoffed. It didn’t sound like music. It was noisy, tinny, reproduction “from a mile away,” as a contemporary put it. In all the excitement of hearing, say, a drum set in a drumless room, one might not notice that drums-as-cylinder are an anemic caricature of the real thing. Where was the attack, the full-bodied thwack, the full crash of the cymbals? No, a lot of work remained. Drums-without-drums were a failure, and the failure is called low fidelity; the recording was disloyal to the original. The goal ever since has been high fidelity.

It’s the year 2000. The world fails to end from a computer glitch, AOL acquires Time Warner, reality television first begins its long war on regular television (and regular reality), and President Clinton is off visiting Vietnam. You enter your dorm room at your prestigious University and find your friend, Richard Pritchard IV, clicking away at your PC. He turns as you enter, waves, and thumbs a knob on your expensive, powerful stereo system. The death throes of an electromechanical bull beaten to death by a six-string guitar fill the room. You shout and make to pull your stereo out of the wall socket, battered by waves of noise with every step, but your friend beats you to it by closing the audio program.

“I didn’t know you bought a Rage Against the Machine CD,” you say, unclenching your teeth.

“I didn’t buy it. There’s this new thing called Napster.”

“Isn’t that a mattress company?”

“Hardly,” he says, ever-patient. “It’s a program that lets your download music from anyone connected to it.”

“Yeah? A lot of use that is, if RATM ends up playing through my speakers. I have to sanitize them now-”

“The program has everything. Every single, every album. It’s a whole new world.”

“Isn’t it stealing to download it without buying it?” you ask.

“They have Radiohead.”

“Move over,” you suggest, and sit in front of your computer.

“I already acquired a few albums, if you’re interested.”

“Wait, how did you download ‘a few albums’ onto my hard drive? Only one gig [of the ten available. Oh, nostalgia. –Ed.] is free.”

“Each album is, like, 80 megabytes.”

“Impossible.”

“Why?”

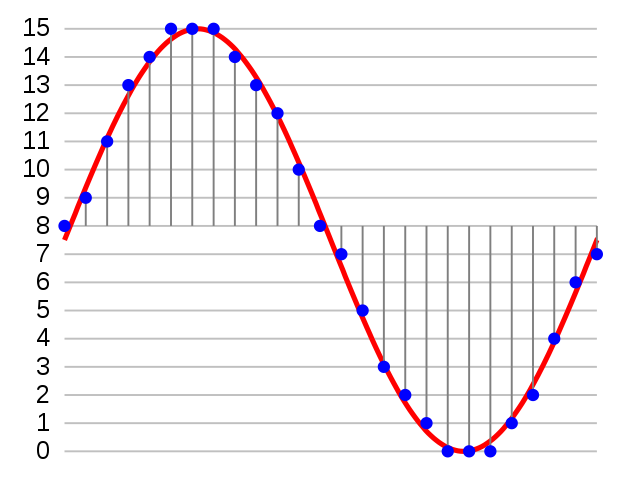

Since you are a huge nerd (not everyone got into the prestigious University through their father’s connections like Richard) you actually know why, and pull over a pencil and a pad of paper. “It used to be,” you begin contemplatively, “that you’d listen to music with your turntable. The quality was good but the records were clunky. They were analog.”

“Analog?”

“Yeah. They recorded sound waves as curves.” You draw a sweeping hill and valley across the paper. “Nature generally behaves like a curve, and sound is no exception. CDs, however, aren’t analog.” You begin drawing more shapes, and your friend leans over to see. “CDs are digital. They don’t use waves; they use numbers that approximate waves.” A series of flat-roofed rectangles now stretch from the bottom of the page to the curve, the Manhattan skyline seen through the cables of the Brooklyn Bridge. At some point of their width, the flat-topped rectangles invariably exceed the curve or fail to reach it. You point to the vertical shapes and say, “Each of these is a digital estimate of the height of the analog wave at that point, and can be expressed as a number.”

“But why wouldn’t you just use the curve itself, like they did on records?”

“They take up too much space. A series of ones and zeroes can say the same thing and take up less room doing it.”

“But it’s inexact!” your friend objects. “Rectangles can’t really imitate a curve.” He points to the wedges of space between the skyscrapers and the bridge. He is right, of course. This is the information in the sound wave that is lost when converting to digital. You begin drawing new rectangles, thinner this time. If the first set were broadswords, these are stilettoes. Though they diverge much less from the curve, the error is still there. And it always will be, “Unless you have an infinite number of rectangles,” says your friend. You raise an eyebrow. “I took calculus in high school,” he explains.

“We don’t need an infinite number,” you say. “We only need 44,100 per second of sound.”

“What?”

“The guys who invented the CD figured out that’s how many you’d need, if you want the digital to duplicate the analog. To the human ear, at least. And that’s why an album can never be 80 MB.” You describe a list of numbers as you write them down. “The rectangles are called samples, because the curve is sampled as a certain number at a certain rate. Here, the rectangle is at this height, and then a second later, it’s at a different height, etc. Each sample is a number, and every number in binary is represented by a certain number of bits. If we only used one bit to store a sample, each one could only have a height of 1, or 0. Not a lot of accuracy there.”

“I hope you’re talking to yourself, because I don’t understand a word.”

“So instead of one bit they used sixteen of them, which yield 216 choices of height. Sixteen bits is two bytes per sample, with 44,100 samples per second, and all of it’s done twice, since there’s two channels in stereo audio.”

“Left and right,” Richard says.

“Correct. Now a full CD runs for 74 minutes. Times sixty seconds per minute…” You hold up your handiwork. The page reads:

2 x 44,100 x 2 x 74 x 60

“Equals,” you say, and tap some numbers into your desk calculator, “783,216,000 bytes. Or around 700 more megabytes of Rage than you claim.” Your tone says, QED.

He grabs the mouse from your hand and conjures up the properties of a CD he downloaded. The screen reads 80.3 MB. Your brow furrows.

“Reality trumps theory,” says Richard with satisfaction.

How boorish.

G-d is omniscient, thank G-d. He knows that my presentation on infinity earlier was full of, well, infidelity. G-d is not infinite in the confined, logical, Aristotelian sense of the word, where “infinite” and “finite” are a contradiction. G-d is what’s called a Kol Yachol, the One who can do anything, whose boundless expression is absolute perfection. This means that if, in his infinitude, he can’t “do” finitude, then He is imperfect, limited to limitlessness. G-d has no limits.

It therefore turns out that G-d exists in some place beyond all conception, and infinitude and finitude are merely modes of his expression. One can be G-d and be non-infinite, the way that there is such a thing as music before any air vibrates or any grooves run. Music itself is ineffable, beyond, and “live” and “recorded” are just two ways of tapping into the same truth. G-d is no more infinite than He is finite, no more spiritual than He is physical, just as it’s nonsensical to say that music is, at its essence, more live than it is recorded. The thing itself is being mistaken for the way it communicates.

This seems encouraging for those of us who don’t have any money for live shows and/or live in a finite, physical, natural world where nothing interesting ever happens. Neither of these is any less “real” than going to the live show or meeting G-d face-to-face. A recording is no less music than a concert; our physical world is no less G-d than whatever existed before He created it. It’s like a game of peekaboo. I cover my face with my hands and ask you, “Where have I gone?” The answer is nowhere. My hands are me just as my face is me, and no concealment has taken place.

Is any of this truly satisfying?

Not in the least.

Are you happy to live life listening to your iPod, never seeing the artists in the flesh? How about living in this world, secure in the knowledge that it, too, is G-dly while never coming face-to-face with its creator?

Wouldn’t we prefer to see His face, and not just His hands?

Weren’t the world and iPods created in the first place for those who can’t handle the real thing?

Compression is one of the boons of the shift from analog to digital audio. The goal of compression is to put the lie to the miscommunication principle; we can have drums without drums. We can even have 700 MB without 700 MB; we can carry thirty thousand songs in the palms of our hands. This is the mp3 revolution.

And, as any audiophile will tell you, it’s a lie.

A lot of the music flying around in the glorious Napster days sounded almost as tinny and reduced as Edison’s wax cylinders. Since mp3 is a form of “lossy” compression, a certain amount of information goes into an mp3 encoder and significantly less comes out the other end. The encoder’s job is to decide which information is relevant and therefore worth keeping and which is not. By discarding details of the sound that (in theory) your average listener won’t miss anyway, the mp3 stuffs an enormous amount of relevant sound in a small place. The lower the bitrate of the mp3, the more information is thrown out.

To which the audiophile would say, “I didn’t realize the music was so easily divided. If the artists decided certain sections of the waveform ought to be in the recording, by what right does a fancy calculus-wielding program strip them out?”

The argument then becomes highly subjective (and violent) and focuses on whether the algorithm does a good enough job at guessing what the human ear can’t hear anyway, and at what bitrate. This often branches (and if it doesn’t it should) into a divisive ideological discussion. Does the near-miraculous process of fitting something huge into a small place deserve recognition as an outstanding intellectual achievement if it yields Beethoven’s Symphonies encoded in a near-skeletal 128 kbps, turning everyone’s music library into a collection of cell phone ring tones?

Everyone agrees, however, that the sound you get from an mp3 is not the same sound they heard at the recording studio. It is, at best, an illusion. Just because David Copperfield said the Statue of Liberty was gone, and it seemed that way to his audience’s senses, doesn’t make it true.

As previously mentioned, G-d can do anything. Don’t go placing any rash bets just yet (if Elvis and Tupac ever ride the Loch Ness monster through Times Square I’ll be writing my next brilliant article in the lap of luxury); He seems to prefer following the rules of logic most of the time. It’s probably related to the aforementioned slice of pizza; if everything that takes place has his fingerprints all over it, could the world ever just exist in peace as the world? If there were no logic, could pizza ever just be pizza? It’d be like a thirty-year-old whose mother still does his laundry: hard to respect.

Instead of direct involvement, so to speak, He uses a system of interlocking translations of His Truth. The physical world, what we call “natural,” is for Him the end result of a long process. He begins with his Truth, his song. We now know that, by definition, only He can hear it; in fact, if you know it like He knows it, congratulations, you must be Him. He then taps into his powers of finitude to capture the same song in a limited form; He wants to put himself into the smallest possible space, which by definition means somewhere utterly removed from Himself. It’s hopeless, you might think. There is a fidelity/space tradeoff. If He wants someone to get the music as-is, he should play them the supernal equivalent of a vinyl record, or a non-compressed CD. This is like saying that if you want to meet G-d, you have to meditate in a monastery for at least eighty years. He can reach as low as the monastery, where the physical touches the spiritual, but he can go no further. If he were to express himself any lower, it could only be as an illusion. His Truth would not be there; some lookalike substitute would have to suffice. He is not portable. If I find him on the subway in Brooklyn, or, Lord help us, Manhattan, it’s not really Him I’ve found. It’s His mp3.

Is there a solution to this quandary?

Humans have found one. It’s called FLAC, the Free Lossless Audio Codec. You read that right. Lossless. That means the files are not going to be as small as MP3s, so it’s a little bit harder to fit them onto your hard drive or your phone. But the files are half the size of the original recordings, and they’re perfect. Drums that can’t fit in your hand go in one end. Drums that can come out the other. For the first time since that wax cylinder was upended on the table, if I play you a song, and then hand you a string of ones and zeroes that make up a FLAC file, I am actually giving you two of the exact same thing. As long as you have a good recording microphone, and the right software, the two are indistinguishable. And the FLAC can take the train.

G-d looks at Himself, and sees: Himself. He looks at the world and sees Himself, too. One is a compressed form of the other, a FLAC inside a .zip inside a .rar inside a .7z. He has all the software He needs to hear the music (his programming ability is world-renowned). He doesn’t even need the infinite, “live performance” version anymore. He has this lossless file. They are the same thing. It’s not just an illusion. If we can make FLACs, then so can He. And so He does.

What’s the point of it, you may be wondering. Why go through the trouble? If to Him the world is merely a reflection of Himself, why create it? It really does seem to be a bad move, if only in its pointlessness. He can see right through his own deception, the same way a really jacked up iTunes could play the 7z[rar[zip[FLAC]]].

The point is that there are those who can’t see through the illusion. Not easily anyway. They are stuck right at the point where they have the file, but not the necessary software. There are those that can’t hear the music.

There are 7 billion of them, actually.

As you look down at your breakfast (eggs fried lovingly; salad), Richard takes the spot next you on the bench in the Yeshiva dining room. “Spend a year in Israel, they said. It’s a man’s life, they said,” he complains.

“Just buy some Cocoa Rice Krispies already,” you suggest, taking a swig of filtered water. The tap water in Jerusalem hurts your stomach.

“Do I look like I’m made of money? Twelve shekels!” He takes a bit of egg and shudders. Richard (he prefers Yerachmiel now) never adapted well to new places. You’d never tell anyone, but you feel a little homesick as well, and you frown as you chew.

“Why the long face?” asks a kind voice. You look up to find one of the rabbis sitting across from you, eating granola cereal. His huge salt-and-pepper beard fans across his neat black sweater vest below a cantankerous moustache. Floating above it all are sparkling brown eyes staring at you through oblong glasses.

“Missing home, I guess,” you answer, shy. You heard he sometimes yells at people.

“You know, G-d is with you more in the difficult times than the easy ones.”

“Ah, sure,” you say, and push some tomato cubes around your plate. The rabbi’s words remind you of some e-mail you deleted once about footsteps in the sand. Richard elbows you in the ribs and you look up to find the rabbi glaring at you.

“It’s true,” he insists, his voice climbing an octave. “Why are we here in this world?”

You shrug. He looks at you like your stern uncle Ezra.

“G-d wants to be revealed even and specifically in the lowest places. He wants to be seen in His infinitude in a place that seems utterly separate from him. It’s like a FLAC file.”

“What?” you and Richard ask.

“Never mind,” he snaps. “Suffice it to say that from His point of view, nothing ever changed. Before a world was created He was alone, and now that it was created He is alone. The difference is all on our end.”

“I prefer after the world was created, since I exist,” your friend pronounces. The rabbi’s beard twitches as if it might fly off and attack the student on its own.

“Since the illusion of an existence separate from G-d is made for us, it’s designed so that we constantly teeter at the point of discovering Him. He is always waiting, just beyond our reach. We are handed code, and told to understand.” The rabbi eats a spoonful of oats and waits for your response, his head cocked to the side.

“What does that have to do with difficult times?” you ask.

“Anything that you can easily see as a blessing, for example those delicious eggs, or my granola, or a good day where everything seems to go your way, is G-d giving you Himself, directly, because you can appreciate it from your perspective. And if you can appreciate it, how great can it be? How much of His Truth is left in it?”

“That’s uplifting,” your friend chimes in.

The Rabbi stabs one of Richard’s eggs with a fork, transfers it to his plate, and begins to eat it. In between bites he says, “You don’t get it. In fact, not only do you not get it, if you were to truly understand, you’d be Him. It’s the miscommunication principle. The only aspects of the Truth you can appreciate are the trifles He can hand you without you totally losing yourself. He lets you hear a whisper of a whisper of His music.”

“Isn’t this like how G-d conceals Himself to give man free choice? Because if He was revealed no one in their right mind would ever choose to do evil?”

“It’s so much more than that,” the Rabbi says, drawing his plate close and thereby thwarting Richard’s attempts at reclamation. “To say He hides Himself to give us free choice is to chalk up our deaf, dumb, blind, G-dless state to an infuriating technicality. What I’m proposing is that we should rejoice in His concealment, because it is the purpose of our existence. We are to look the illusion of His absence straight in the eye and tell it that we don’t believe in it, that no matter what our senses tell us, the world is G-dly. And G-d is good. We must demand to see it from His perspective. His endless symphony plays all around us.”

“What happens once we do that?” asks Richard.

“When G-d realizes that He doesn’t see the illusion, and that we aren’t fooled by it, it no longer serves any purpose. So He takes it away.”

There once was a great sage who asked a young child why he was crying. “My friends and I were playing hide and seek,” replied the child. “But I hid myself so well that they gave up looking for me.” Said the sage, “This is how G-d feels about His creation.” Our world is so much more than the two-bit manipulation of the material. If we use the right software, the right perspective, we’ll see that G-d Himself has been here all along, waiting impatiently to be found.

There is so much more to say.

We could talk about how the difference between a data stream and a live music show is really the difference between the natural and the miraculous, how nature itself is a lie. We could talk about how withstanding the great tests that G-d places before us, like the forefather Abraham did, is the ultimate purpose of the illusion and, therefore, of life, since it is the crucible where nature clashes most strongly with our will and duty, and passing a test literally creates miracles because it itself is in violation of nature. We could talk about the Big Lie, how we’re told by our world in a million different ways that it’s the ones and zeroes that are important, that whoever manipulates the data best will achieve happiness, that there is no underlying music and the search for it will fail, and that if you must search for G-d don’t G-d forbid let it get in the way of your success in the field of binary manipulation. We could talk about the incredible strength and joy that the G-dly perspective lends to one’s life, since there are no setbacks, there is no darkness, and He not only runs the world but the world in fact has no existence apart from His truth. Maybe in the future we will talk about all of these things, but for now, this long screed has come to an end.

All of what I just told you has been sitting in holy books written in Hebrew for over a hundred years, by the way. You might wonder – why not just have you read the original sources? Why write so many words? Why bother with tortured examples from the world of music and with whimsical multi-generational fiction?

I thought you would appreciate why by now.

Hebrew without Hebrew is so much better.

Wouldn’t you agree?

audio communication extended metaphor fiction mysticism technology unity

Previous Next